4-23-12: Shakespeare Day

24/04/2012

Happy birthday, Shakespeare. And my condolences on your death. Still, for a guy who’s been dead for near four hundred years, you’ve got a lot going on. The World Shakespeare Festival kicked off last night.

Venus and Adonis traveled all the way from South Africa yesterday. The rainbow nation sent a multi-colored and multi-lingual presentation of the erotic poem telling the story of the goddess of love and her reluctant boy toy.

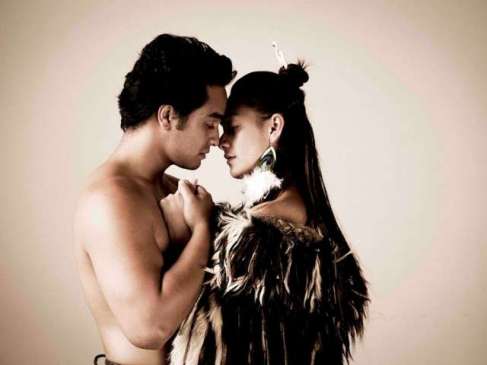

Today Troilus and Cressida come from New Zealand for rancid romance in Maori.

How do you say, as Cressida says to Troilus while succumbing to his suit, “In that I’ll war with you” in Maori? Does it sound as sluttish as it can in English–“war” punning “whore”? I wish I could hear it, even if I wouldn’t understand it. I wish I could hear and see the haka battle dance of the Greek and Trojan armies. It looks so cool. It looks like it sounds so cool.

I wish I could be there for the Israeli Merchant of Venice (in spite of the conflict surrounding it), the Balkan Henry VI trilogy, the South Sudanese Cymbeline. I’ll really miss the Globe’s Globe-to-Globe, but I’ll catch some of the WSF later in the summer.

Meantime, Mr. Shakespeare, I’m re-viewing a performance of the play that made me follow your work. Macbeth. The Patrick Stewart one. I should really say the Rupert Goold one. Patrick plays Maccers marvelously (and Kate Fleetwood destroys Mrs. M, in the best possible way), but it’s Goold’s show.

Goold’s setting of your story in a Stalinist/Soviet-esque military dictatorship may not be original, but it worked. I saw it on Broadway, after it transferred from the Brooklyn Academy of Music. After in transferred from the West End. After it transferred from Chichester. Yeah, it transferred a lot. It was that good. Nicholas de Jongh called it “the finest Macbeth I’ve ever seen.” That actually means something, from Nicholas. (He tends towards the harsh.) I don’t know if it was the finest Macbeth I’d ever seen, but given all those transfers, and the filming, which aired on PBS before being released on DVD, it must be among the most successful Macbeths ever.

I liked it a lot in the theatre. I like it even better on screen. Goold doesn’t just film his staging; with director of photography Sam McCurdy, he transforms the mis-en-scene, bounding over the media barrier and landing with a bang. With a lot of bangs, actually. If you watched it during one of the live runs, the ending will astonish you. If you didn’t, the ending will still astonish you. I won’t spoil it. Just check it out.

5-23-2011: Hogwarts Hamlet

23/05/2011

Another Harry Potter viewing prompts another post. I know I’m not the only one to notice, but while watching The Half Blood Prince, I couldn’t help but comment on the striking resemblance Draco Malfoy bears to a certain Moody Dane.

The visual parallel is obvious– blond, black, duh– and so is the surface similarity of narrative– young man seeking revenge for father– but more fun is matching up the moments of Malfoy with lines from Hamlet.

Gazing agonizingly into the mirror.

‘To be or not to be…’ (Ripped right from Branagh)

Contemplating a dead bird.

‘There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow.’

Duelling with Harry.

‘A hit! A very palpable hit!’

Pointing his wand at Dumbledore.

‘Now might I do it pat.’

5-6-11: Star Wars and the Bard

06/05/2011

4-29-11: Hamlet (Philly Shakes)

29/04/2011

Okay, so obviously my intention to blog the Sonnets this year has kind of petered out. However, last night I attended the Philadelphia Shakespeare Theatre’s production of Hamlet, and my while my girlfriend and I were discussing it afterward, she suggested I write and post about it, and that I turn this blog towards more generalized Shakespeare coverage– not just the Sonnets but whatever kind of Shakespeare Shit comes my way. My girlfriend has good ideas.

So, Hamlet. Interestingly, it’s been exactly five years– to the day– since I attended my first full Hamlet— a South African production visiting Stratford-upon-Avon. I’ve witnessed a lot of different interpretations: Hamlet in a Horror House with hard rock music accompaniment; Hamlet performed by a cast of international students, including an Australian Claudius, a French Gertrude, and a Russian Prince of Denmark; a two-man Zimbabwean Hamlet half in English, half in Shona; the Royal National Theatre’s multi-award-winning Hamlet… and that’s all in the last year–go further back and I can count the modern-dance, silent Hamlet, the tiny ninja action figure Hamlet… But back to Philly Shakes. This Hamlet’s Big Idea was to feature a female Dane. I knew that coming in, but I didn’t know the actress, Mary Tuomanen, is also playing Rosalind in PST’s other offering this season, As You Like It. Doubling these two roles–written at roughly the same time– makes for a neat exploration of the characters, and a nifty poster to boot!

Interestingly, director Carmen Khan seems uninterested in commenting heavily on her creative casting, at least in the Hamlet half of the repertoire. Tuomanen plays Hamlet as a man, with no attempt to emphasize or ironize any gender issues, even such potentially loaded lines as ‘Frailty, thy name is woman!’ I confess I’m kind of glad for the straight (pun intended) approach. If Khan had tried to invest the show with a lot of keen conceptual insight, either she would have failed, which would have been distracting, or she would have succeeded, which would probably still be distracting. As is, I’m able to ignore, even occasionally forget about Tuomanen’s biologic identity and just enjoy a very fine delivery of arguably the best role written in dramatic history.

Tuomanen is lithe and light on her feet, her LeCoq training obvious in her energy and graceful gestures, and she is no less adept in her verse- and prose-speaking. The words do indeed trip off her tongue (even if Khan does cut that speech– one of a number of judicious textual trims keeping the evening to two-and-a-half hours), and she manages the delicate balance between relishing the poetry and keeping the communication real. Actually, my girlfriend said she was impressed by how fresh and earnest the lines felt, which she attributed at least partially to how young the Prince came across. I agree, and applaud Tuomanen’s matching of genuineness with playfulness.

Kahn’s casting boasts other strengths, including an impressive Claudius from Ames Adamson. Adamson occasionally errs on the side of chewing the scenery, but given the usurping King is a bit of a pompous ass, that’s perfectly appropriate. Amanda Grove and John Little give solid readings of Gertrude and Polonius, respectively, and Victoria Rose Bonito brought tears to my eyes in her portrayal of Ophelia’s madness. Probably the most memorable image in the production is poor Ophelia laying a headless doll, dressed (like herself) in a white wedding dress, into the pool occupying center-stage. Anyone familiar with the play (and who isn’t?) will be struck by the fore-shadow of her imminent drowning. So beautifully sad.

This Hamlet’s world is well-designed. David Gordon’s stark, charcoal floor and walls evoke Elsinore nicely, with Vickie Esposito’s contemporary clothing somehow complementing rather than clashing with the more medieval swordplay– tidily choreographed by Mike Cosenza.

All in all, I’m thoroughly engaged. I last visited Philly Shakes four years ago, for Othello. This time I won’t wait as long to return– I want to catch Tuomanen’s Rosalind before As You Like It closes!

3-24-11: Sonnet 40

24/03/2011

Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all;

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call;

All mine was thine before thou hadst this more.

Then if for my love thou my love receivest,

I cannot blame thee for my love thou usest;

But yet be blamed, if thou thyself deceivest

By wilful taste of what thyself refusest.

I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief,

Although thou steal thee all my poverty;

And yet, love knows, it is a greater grief

To bear love’s wrong than hate’s known injury.

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites; yet we must not be foes.

Last night I was watching Harry Potter 3 and recognized the lyrics sung by the Hogwarts choir as coming from Macbeth. The young witches’ and wizards’ rendition of ‘Double, double, toil and trouble’ inspired me to recall musical versions of the sonnets. Number 40 stands out as I’ve heard two separate scorings.

One was during a production of Love’s Labour’s Lost by the Shakespeare Theatre Company of Washington D.C (2006). Director Michael Kahn staged the play in the 1960s, making the King of Navarre and his three friends a rock band, like the Beatles, who swear celibacy and study. In this scene, however, they’re in the process of breaking their oaths and writing sonnets to their chosen loves. Only they don’t stop at writing sonnets; Kahn has them compose complete love songs. It’s hard to describe just how awesome this is, but I’ll do my best. It starts with Hank Stratton’s Berowne, strumming his guitar and humming: ‘Rosaline, O Rosaline… You look fine, O Rosaline!’ It continues with Erik Steele’s Longaville, who wheels out an entire drum set and bangs out his ballad—’My vow was earthly, thou a heavenly love!’—and Aubrey Deeker’s Dumaine, who jams on his bass—’On a day—alack the day—Love, whose month is ever May, spied a blossom passing fair, playing in the wanton air.’ Dumaine is gradually musically joined by Longaville, Berowne and even Amir Arison’s King, who dances and waves a tambourine, and the scene culminates in a full-fledged concert featuring Number 40 and a lot of psychedelic flashing lights. Rock on!

The other was during a joint project presented by the Royal Shakespeare Company and Opera North (2007). Multi-talented Irish artist Gavin Friday, pimped out in a bright red shirt, platform shoes, bling rings and chain, sauntered center-stage and groaned the sonnet into the microphone, arriving at a falsetto climax—’Kill me with spiiiiiite’—that was a little silly and a little sexy and very entertaining.

Just goes to show how differently texts can be interpreted by performance.

O, and on a poetical note, take a close look at line 8: ‘wilful taste’—will-full taste—taste full of will, of Will. What word play! You are at fault, the speaker says, if you lie to yourself by seemingly rejecting what you actually relish—the taste of the author!

14-2-11: Sonnet 116

14/02/2011

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come:

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

A few years ago, a good friend of mine asked me to read something at his wedding. I combed through the canon, searching the sonnets and the plays for glowing endorsements to marriage. There aren’t many. If any.

The debate amongst scholars and fans continues as to whether or not Shakespeare loved his own wife, Anne Hathaway. Theirs seems to have been a shotgun wedding– the older, wealthier woman well along in pregnancy, presumably with Will’s baby. Shakespeare spent most of his time in wedlock out of town, and when he died, he bequeathed his nuptial partner and the mother of his children only the second best bed. That could be a sign of affection—often the best bed was reserved for company, while the couple slept together in the second best—but it smacks of irony, at least.

There’s irony too in many of the references to marital relations in his works. Consider one of my favourite lines from the end of Henry V, in which Queen Isabel of France blesses the upcoming union of her daughter, Princess Katherine, with Henry: ‘God, the best maker of all marriages, combine your hearts in one, your realms in one!’ Anyone who’s familiar with the History plays, or just history, knows what happens between France and England, rendering Isabel’s words rather loaded.

But, you may protest, Shakespeare was a poet of love! He wrote so many wonderful romances. Yeah, but think a little harder about the couples he creates. Often the women are markedly more interesting and intelligent than their other halves. Are the brilliant Rosalind and Viola really likely to be happy with the insipid Orlando and Orsino? What about the bickering Benedick and Beatrice? Is the mutual abuse practiced by Petruchio and Katherine going to make for stable, healthy companionship? Don’t get me started on Romeo and Juliet, or Troilus and Cressida, or even Antony and Cleopatra. Actually, the happiest partners could be the partners-in-crime, the Macbeths. At least until they murder Duncan.

Anyway.

This sonnet is as close to commenting positively on a committed relationship as I could find, at the time. And the marriage to which it refers is probably metaphorical—‘of the mind’, not necessarily of the state, or church. Still, it is lovely. I offer it now in honor of Valentine’s Day.

28-1-11: Sonnet 103

28/01/2011

Alack, what poverty my Muse brings forth,

That having such a scope to show her pride,

The argument all bare is of more worth

Than when it hath my added praise beside!

O, blame me not, if I no more can write!

Look in your glass, and there appears a face

That over-goes my blunt invention quite,

Dulling my lines and doing me disgrace.

Were it not sinful then, striving to mend,

To mar the subject that before was well?

For to no other pass my verses tend

Than of your graces and your gifts to tell;

And more, much more, than in my verse can sit

Your own glass shows you when you look in it.

I know this is taking it out of context, but the first line makes me laugh. O starving artists. Right now I’m half-watching a friend play Assassin’s Creed II, and his character is being followed around by an irritating Italian troubadour playing some stringed instrument and begging for loose change.

At least Shakespeare died rich. Unlike so many of the greats. Poor Mozart, buried in a pauper’s grave. Shakespeare and his family occupy a goodly portion under the floor of his home church.

However, like so many of the greats, Shakespeare doubts, or at least expresses doubts, about his powers. Which is the real point of sonnet. How can the Speaker improve, or even dare to try to improve, on the beauty of the Desired? It’s impossible, and it may even be wrong. If, as according to Hamlet, the purpose of playing (and art) is to hold, as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature, then attempting to adorn the simple reflection of reality is ‘from’ (contrary to) that purpose.

Take a look at line five. A single sentence. Rare, in the sonnets, for a sentence to stay on one line. And anything unusual probably deserves particular emphasis. As does any phrase beginning with ‘O’. So if you’re acting, or reading aloud the poem, speak this line with special feeling.

21-1-11: Sonnet 69

28/01/2011

Those parts of thee that the world’s eye doth view

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend;

All tongues, the voice of souls, give thee that due,

Uttering bare truth, even so as foes commend.

Thy outward thus with outward praise is crown’d;

But those same tongues that give thee so thine own

In other accents do this praise confound

By seeing farther than the eye hath shown.

They look into the beauty of thy mind,

And that, in guess, they measure by thy deeds;

Then, churls, their thoughts, although their eyes were kind,

To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds:

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this, that thou dost common grow.

I used this sonnet as an audition monologue once. As expected, the director asked me to try it several different ways, which was great, because it’s a versatile piece of poetry. It can be done as an accusation, an angry upbraiding of faithlessness (A). It can be done as a plea, a desperate begging for restoration (B). It can be done any number of ways in between. I didn’t get that gig, but I enjoyed playing with the text.

It begins with words of praise, of typical hyperbolic adoration, but the compliments are shortly revealed to be backhanded. The outward parts may be flawless, peerless, and universally so-acknowledged… but… by the time the speaker finishes, he’s comparing the subject to shit

I was inspired to pick 69 as an audition piece during one of John Barton’s workshops. He had actor Geoffrey Streatfeild work with it.

Streatfeild’s voice was perfect for the part. Sometimes smug, sometimes sullen, always silky smooth, whether indicting or insinuating, he filled the fourteen lines with such scorn and disdain I shivered. I wish I could achieve a fraction of that derision.

14-1-11: Sonnet 86

14/01/2011

Was it the proud full sail of his great verse,

Bound for the prize of all too precious you,

That did my ripe thoughts in my brain inhearse,

Making their tomb the womb wherein they grew?

Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write

Above a mortal pitch, that struck me dead?

No, neither he, nor his compeers by night

Giving him aid, my verse astonished.

He, nor that affable familiar ghost

Which nightly gulls him with intelligence

As victors of my silence cannot boast;

I was not sick of any fear from thence:

But when your countenance fill’d up his line,

Then lack’d I matter; that enfeebled mine.

Act it. Treat the sonnet like a monologue, RSC co-founder John Barton instructs. Many, if not most of them work this way. Who is speaking? To whom? For what purpose? Approaching the verse dramatically rather than literarily helps penetrate the sometimes dense meaning. Try it. You’ll like it. Or listen to me try it.

The Speaker rails against the Desired who has, apparently, appeared in a rival’s poetry. Now the Speaker is poetically silenced. Writer’s block. (And maybe more? To put it in crude, contemporary sexual terms, is there some cock block here as well?) It’s not the rival’s talent, the speaker protests—that’s probably unnatural anyway, the product of an illicit, otherworldly collusion. It’s that the rival uses as muse the Desired—that hobbles the poor poet.

Of course, the fact that the speaker is complaining about not being able to write by writing a beautiful poem is ironic, to say the least. But Shakespeare was never known for logical consistency…

O, and this is extremely nerdy, but the internal and antithetical rhyme of ‘tomb’ and ‘womb’ is way too cool to pass unremarked upon…

11-1-11: Sonnet 113

12/01/2011

Since I left you, mine eye is in my mind;

And that which governs me to go about

Doth part his function and is partly blind,

Seems seeing, but effectually is out;

For it no form delivers to the heart

Of bird of flower, or shape, which it doth latch:

Of his quick objects hath the mind no part,

Nor his own vision holds what it doth catch:

For if it see the rudest or gentlest sight,

The most sweet favour or deformed’st creature,

The mountain or the sea, the day or night,

The crow or dove, it shapes them to your feature:

Incapable of more, replete with you,

My most true mind thus makes mine eye untrue.

When my girlfriend and I had to be separated by the stupid Atlantic Ocean for a few months, I found myself with this sonnet a lot. Again, it’s obsessive. The hyperbolic replacement of Every Thing in the speaker’s view with the absent desired is a bit too extreme, perhaps, but I can definitely relate to the underlying sentiment.

It wasn’t so much that everywhere I looked I saw her. That would be weird. But wherever I looked, whatever I did, I wanted to share with her. Beauty was still beautiful; fun was still fun; but not as much as if she had been with me. The brain belies the eyes, dulling the otherwise vivid sensations because of the missing stimulus.

Thank goodness for email and Skype, eh? I can’t imagine what it would have been like when comparatively long-distance correspondence was by boat, if you were lucky enough to be in a mutually literate relationship. Methinks parting then was heavier on the sorrow than on the sweet.

By the by, how am I choosing which sonnets to blog? Well, I may follow an impulse to write about a particular poem on a particular day. It seemed appropriate to start with my favourite (60) for instance. Or I may pick one randomly – like last time. Or I may follow the previous entry – like this time. (I know, I know, I should’ve written about 111 on 11-1-11…) Though there seem to be cycles, groupings of similarly themed or addressed poems (the ‘Dark Lady’ cycle, for example), there’s no absolute evidence that Shakespeare composed the sonnets in any specific order, apart from the sonnets that clearly follow each other. (112 and 113 are not examples; 113 and 114 are.) I had hoped to blog three a week, completing the collection by the end of the year. But best laid plans…